The Jewish Community of Herat, Afghanistan

Dedicated to the Memory of Werner Herberg

A Research Trip to Afghanistan

Introduction

Nevertheless, in Tabakāt-i Nāsirī the main source for the Ghūrids, the thirteenth-century historian al-Juzjani (al-Ğūzğānī) refers to a Jewish merchant, a Yahūd (Jew) from Ghūr. According to the source, this Jewish merchant had acquired great experience in the ‘ways of the world and he entertained a friendship with Amīr Banjī, one of the founders of the Ghūrid dynasty.[1] The friendship started with the incident that took place when Amīr Banjī was travelling to Baghdad to resolve a dispute with his enemy. He met the Jewish merchant and asked him for some advice, which, in the event, turned out to be quite valuable. Amīr Banjī felt grateful to the Jewish merchant and let a number of the “Children of Israel” (‘Banī-Isrā’īl’) settle in his territory. The chronicle gives us some insights into a rationale for the existence of the Jewish settlement in the region although there is no conclusive evidence that these Jewish merchants were related to the speakers of the JudaeoPersian dialects. Medieval sources refer to several Jewish centers in Afghanistan; from which the most important were located in the cities of Merv, Balkh, Kabul, Nishapur, Ghazni and Herat.

In his work, 'Siyásat-náma', the medieval Persian author and celebrated vizier of the Great Seljuq Empire, Niẓām al-Mulk, (also known as Abū ʿAlı̄ Ḥasan ibn ʿAlı̄: 1018-1092 CE), already noted Jewish service in Muslim royal courts.[2] Written in 1091-1092 CE, the work Niẓām comprises fifty sections treating nearly all of the royal duties, prerogatives, and administrative units during the early Seljuq period. According to the record, Niẓām al-Mulk himself emphatically rejected the employment of “dhimmī” referring to "Peoples of the Book", which included Jews, Christians, Sabaeans, and sometimes Zoroastrians and Hindus, in governmental service.[3] Thus, he complains bitterly

"…that Jews, Christians, Fire-worshippers (gabrs), and Carmathians are employed by the Government, and praises the greater stringency in this matter observed in Alp Arslán's[4] reign."[5]

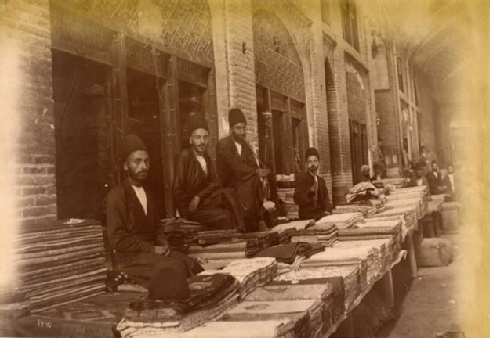

At the same time, however, Niẓām al-Mulk maintained close associations with Jewish bankers and money experts, officeholders, and tax-farmers, who had been called upon to assist him. These non-Muslim minorities were deprived of social and political equality, which made them "second-class" citizens in general - but as dhimmīs, they also enjoyed complete freedom to participate in various economic opportunities. Various Muslim and Hebrew historical sources mention that Persian Jews engaged in many kinds of artisanship and handicraft, working as weavers, dyers, gold and silversmiths, merchants and shopkeepers, jewelers, and wine manufacturers as well as dealers in drugs, spices, and antiquities.[6]

Nizámí-i-'Arúdí,who was a poet, astronomer, and physician in Samarqand, mentioned a Jew named Ya'qúb ibn Isháq al-Kindí in his Chahár Maqála .[7] Nizámí-i-'Arúdí was a champion of various scholastic achievements in the Ghūr empire, who was “attached to the service of the House of Ghūr or ‘Kings of the Mountains.”’[8] The Jew he mentioned in his book was known as "the philosopher of the Arabs" around 873 CE. [9]

"Ya'qúb ibn Isḥáq al-Kindí, though he was a Jew, was the philosopher of his age and the wisest man of his time, and stood high in the service of al-Ma'mún. One day he came in before al- Ma'mún, and sat down above one of the prelates of Islám. Said this man, "Thou art of a subject race; why then dost thou sit above the prelates of Islám?" "Because," said Ya'qúb, "I know what thou knowest, while thou knowest not what I know."[10]

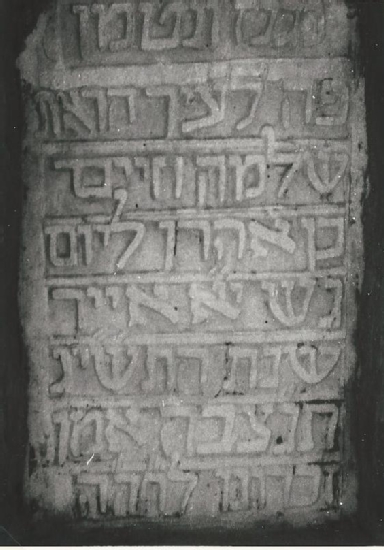

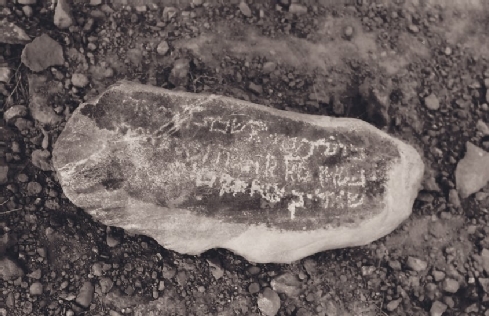

The existence of a Jewish settlement in the remote Muslim region surrounding Djām, the most important Ghūrid site in central Afghanistan, located 215 km to the east of Harāt some 6,234 feet (1,900 m) above sea level surrounded by mountains rising almost 11,483 feet (3,500 m), seems to be enigmatic.[11] The site was extensively studied by David Thomas and his organization, the Minaret of Jam Archaeological Project (MJAP), for the last fifteen years.[12] The city of Djām was a vibrant center of sophisticated urban life under the Ghūrid overlord, Ghiyāth al-Dīn Muḥammad bin Sām (d. 1203 CE).[13] The city is well known for the Minaret of Djām with its elaborate qur’ānic inscriptions,[14] as well as for the discovery of the Jewish cemetery nearby at the Kūh-i Kushkak (Figs.2-4). The Jews might have settled there due to the development of extensive trade networks in this region. The region of Djām, which was the home of the sultan’s summer capital, Fīrūzkūh, was a flourishing politico-economical center, which extended from Nishāpur in Eastern Iran in the west, to the Gulf of Bengal in the south, and Sind in Northern-India in the northeast. The abrupt decline of the Ghūrid Empire seems to have been caused by the death of Mu‘izz al-Dīn Muammad b. Sāms’ in 1206 CE, followed by the conquest of Khwārizm Shāh in ca.1215. Seven years later the Mongol invasion by Ögödei, put a complete end to the whole empire in ca.1222. This region is also well known historically for its flourishing commerce based on iron- and metal processing, and horse breeding as well as slave trading in the markets of Herat and Sistan.

Jews living under the Ghūrid Empire seem to have occupied high functions and positions. During the reign of Sultan Mahmud of Ghazna (997-1030 CE), a Jew living in Ghazni called ‘Isḥáq the Jew’ administered a lead mine in Balkh (Khurasan), having been sent there by the court-poet Nizámí-i-'Arúdí of Samarqand. This court-poet actually received this lead mine in Warsád (the ‘territory of Warshādah’) as the reward for his poems submitted to the local governor, ‘Amíd Safiyyu’d-Dín. Warsád is also mentioned as the residence of king ‘Quṭbu'd-Din Muhammad’ in Ghūr:[15]

"Thereat the countenance of my lord the King brightened mightily, and a great cheerfulness showed itself in his gracious temperament, and he applauded me, saying, ‘I give thee the lead mine of Warsá from this Festival until the Festival of Sacrifice. Send thine agent thither.’ So I sent Isaac the Jew. It was then the middle of summer, and while they were working the mine they smelted so much ore that in the seventy days twelve thousand maunds of lead accrued to me, while the King's opinion of me was increased a thousand-fold. (…)"[16]

At the beginning of the tenth century, permanent multi-ethnic settlements of merchants existed in the region like the trading centers in Kabul and Ghazna during the Ghaznavid era.[17] The English historian and Orientalist Bosworth mentioned that stable Indian merchant colonies also existed even before the establishment of the ancient Ghūrid capital Firuzkuh in (d. 541 A.H./1146-7 CE).[18] The expatriate communities of merchants and their families from Khwarazm and Transoxania throughout Asia were also known to be operating as trading banks with an established system of letters of credit, which were honored in extensive regions from China to the Volga. The Central Asia cities along the Silk Road were serving as main trade posts throughout the region, connecting the west and east with Afghanistan at the mid-point of these extensive trade routes.

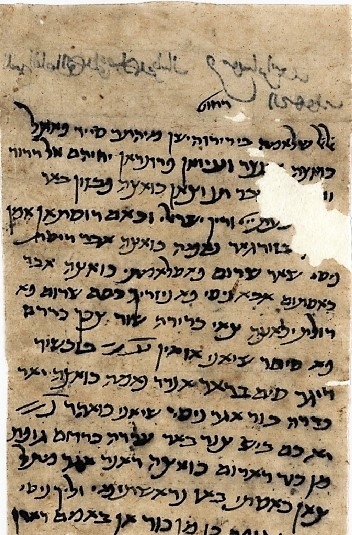

What is the “Afghan Genizah”? A short guide to the collection of the Afghan Manuscripts

The Cultural History of the Jews from Herat

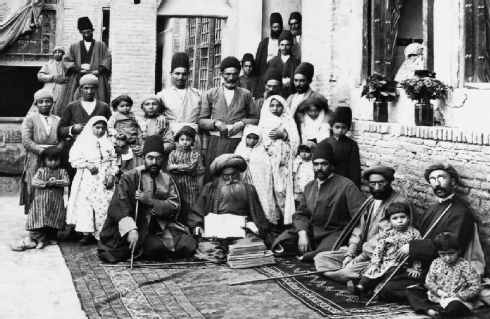

The Jews of Herat are culturally connected to the Jews of Iran. Many Jews once living in Herat were immigrants from Mashhad, generally considered to be the holiest city in Persia.[7] Mashhad’s Jewish community was founded during the reign of the Persian ruler Nadir Shah (r. 1736–47),[8] who was known for his tolerance toward Jews. Following his settlement policy the increasing presence of hundreds of Jewish families helped strengthen existing Jewish institutions and contributed to the flowering of Jewish life in Afghanistan.[9]

"Anusim", a Film and Short Historical Explainer by Illustrator and Director Sohini Tal

The term “Crypto-Jew” has now become the more politically correct term, and refers to all Jews forced to adopt a certain religion and political philosophy while maintaining Jewish practices in secret. Especially in modern times, outwardly Muslim Crypto-Jews are known to be in Afghanistan, Iran, and Turkey.

Even though the forced converts outwardly embraced Islam, the majority of the converted Jews or jadid-e Islam (“new to Islam”) secretly continued to practice Judaism for well over a century as “crypto-Jews” in secret underground synagogues. The forced converts, however, who refused to lead a double life fled to Herat. They intermingled with the large Jewish community there. Later, during the early decades of the twentieth century, Mashhad’s forced converts publicly returned to Judaism.[13] Further waves of hostility toward Jewish communities followed during and after the final takeover in October 1856 of Afghanistan’s provincial capital, Herat, by the troops of the Qajar Prince, Sultan Murad Mirza. The Jews living in the city of Herat—the majority of whom were Mashhadis who settled in Herat following the pogrom of March 1839—were threatened, beaten, robbed of their possessions, and finally expelled from Herat and sent to a camp near Mashhad, in modern-day Iran.The Persian authorities officially justified the ill treatment and expulsion of the Jews on the grounds that the Jews living in Herat had migrated from Mashhad in 1839 without any government permission. The resulting deportations began on the nineteenth day of Shevat 5617 in the Hebrew calendar (February 13, 1857) and lasted about thirty days. Many of the deportees, who numbered 3,000 through 5,000, perished due to hunger, sickness, violence, and the extreme cold. Upon their arrival in Mashhad, the Herat Jews were interned in a dilapidated fortress named "Baba Quadrat". This place was located on the city’s eastern outskirts. The deportees were subjected to extreme physical and economic hardship. After nearly two years of detention, Nasir al-Din Shah (r. 1848–96) permitted the Jews — both immigrants and deportees from Afghanistan and Iran who decades earlier had been forced to resettle in Herat and Mashhad — to return to Herat. Nasir al-Din Shah sealed their fate: unable to regain territory lost to Russia in the early nineteenth century, however, Nasir al-Din Shah sought compensation by seizing Herat in 1856.[14] During the conflict, more than 300 Jewish detainees died from starvation, inadequate clothing, and poor housing and sanitary conditions. Some of the exiles remained in Mashhad, but the majority returned to Afghanistan.[15] This immane (inhumanely cruel) period ended in August, 1858 thanks to British pressure placed on the Persian government. The Jews reached Herat on the thirteenth day of Shevat 5619 (January 18, 1859) and began to re-occupy their former homes.[16]

"These people live in utmost hardship and poverty. Concentrated together in a quarter of the city known as mahalah-yi Yahud, namely the Jewish quarter, they are compelled to build the doors of their houses so low that only by bending is one able to pass through them. The reason for this is that in the event they are attacked suddenly, they will be able to barricade themselves behind the doors easily. Some of the governors and their subordinates use any kind of real or fictitious offence committed by a Jewish individual as an excuse for extorting money from the entire community. Similar pretexts are exploited in order to increase the amount of the poll-tax (the jizyah) established by Muhammad* to be paid by non-Muslim subjects. This continuous oppression and pressure has compelled many Jews to emigrate to Turkey and to other lands in the East, even though the government prevents this emigration in various ways; as a result one can emigrate from the country only by resorting to secret escape-routes."

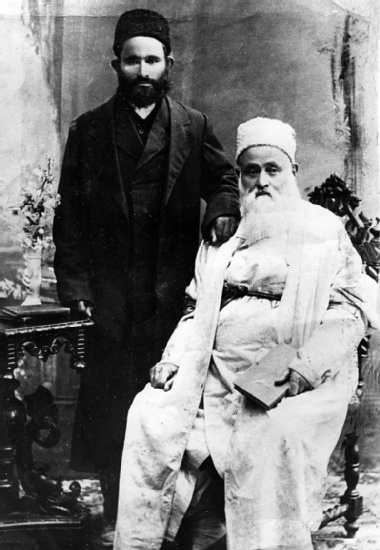

It is worth mentioning that he and his brothers were the only Jews who were permitted to own a stable and ride horses in Tehran (ca. 1870). Moreover, his coveted position and resulting wealth, which was exceptional in the Jewish community, allowed him to construct a synagogue and a clinic in the Tehran’s Jewish Quarter.

As for common people, the stigma of “impurity,” as well as mandatory observation of Jewish religious and legal restrictions built strong motives behind their voluntary conversions to Islam. During this period of instability, financial and social issues were serious causes for conversion to Islam. Among the main motivations for these voluntary conversion to Islam were financial issues depriving Jews of legal and business rights for making transactions with Muslims. The Law of Apostasy, for instance, allowed Muslim members of the family be the sole recipients of the family inheritance. Among other incentives for conversion to Islam, we can find the danger of exclusion from the larger Muslim community, obligation to wear certain attire and identification patches, and lack of protection by the authorities even towards prestigious positions, like private physicians serving the royalty or the public in case of malpractice.

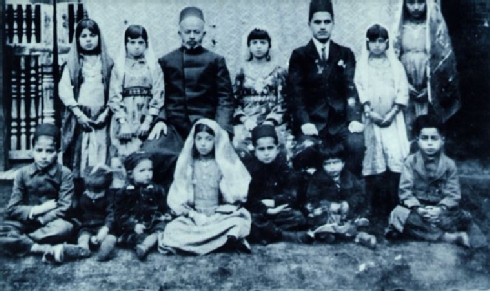

There are various estimates regarding the extent of the Jewish population on the territory of Afghanistan at the beginning of the 20th century. To the figures, once reported by the leaders of the Jewish communities in Afghanistan in the late 1940's, a few thousand must be added who by then either had emigrated to Israel or settled in other regions of the world, mainly in Central Asia and India. The total number of Afghan Jews at the middle of the 20th century could raise about 10,000 individuals. A similar controvery refers to the number of Jewish communities once living in Afghanistan. The two main Jewish communities of Afghanistan were located in the cities of Kabul and Herat, each of them numbering about 2,000 Jews during their peak days in the 1930's. The city of Balkh, for example was home of the third largest Jewish community. The community was made up of many Jewish immigrants originating from Central Asia. Smaller Jewish communities once lived in the towns of Gazni and Kandahar.

Each of the three main Jewish communities still living in Afghanistan after the 1950's - i.e. the Jewish communities in Kabul, Herat and Balkh - had a community council (Hevrah). The community council took care of the needs, organized burials, represented the community in matters connected to the authorities and responsible for paymet of taxes. From 1952 Jews were excempt from military service. Instead they had to pay a special tax (har bieah).

The Jewish Quarter of Herat

The Jewish Quarter of Herat was located within the walled section of the Old City and extended through the smaller streets on both sides of the main thoroughfare of the Bazaar-e Iraq, which leads directly to the Chahar Suq.[23]The economic heart of Herat’s Jewish Quarter was located on the main thoroughfare through the Bazaar-e Iraq among the coppersmiths, ironsmiths, grocers, and hardware stores. It was near the western Iraq Gate, not far from the bazaars at the end of the northwestern thoroughfares that served the caravans traveling between the western provinces of Afghanistan and Iraq.[24]

Jewish Clothing

The Israel Museum's collection of Jewish clothing titled "When Jews Wore Burkas: Exhibition Showcases 19th Century Jewish Fashion 19th Century Jewish Fashion" representing styles worn by Jewish women in North Africa, Yemen and Asia, was showcased in NYC in 2017.

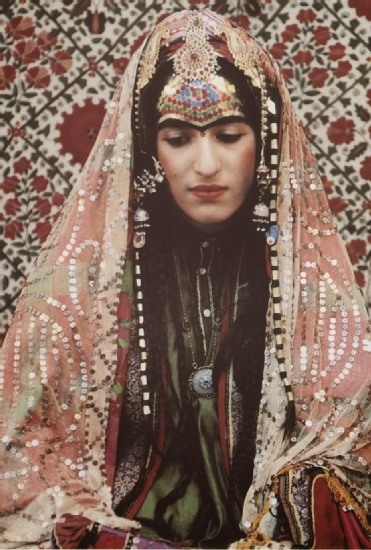

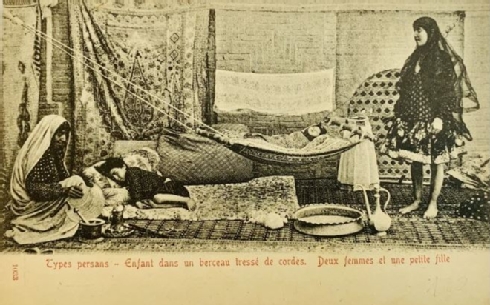

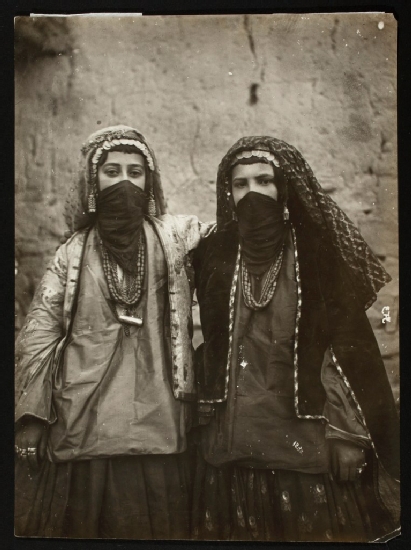

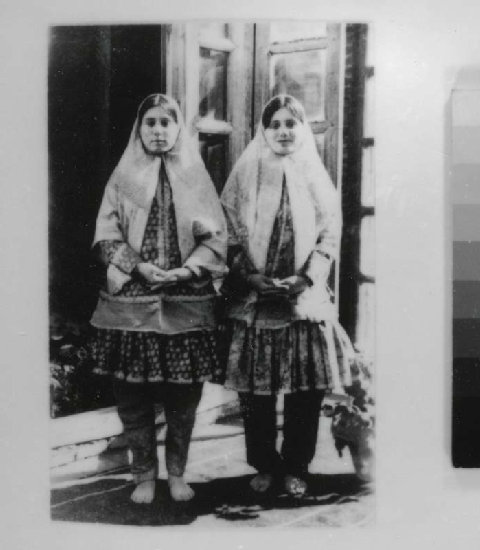

Jewish women in Herat, Afghanistan were dressed in the style of the surrounding society. They wore a large or small rectangular headscarve, commonly called čādar (chador), with or without small hats similar to the men’s kolāh, that were worn under turbans. The chador was made of soft cotton, often but by no means always in a solid color.

In Mashhad, Iran, Jewish women wore the chador along with a veil. They were dressed just like their Muslim neighbors. After they fled persecution and forced conversion in the 19th century and resettled in Herat, Afghanistan, the Jews originating from Mashhad, however, preserved their Iranian-style shawl. Thus they avoided to adopt the local burka like their Jewish contemporaries in nearby Kabul. Many Jewish women continued to wear the chador until their immigration to Israel, as late as the 1970s.

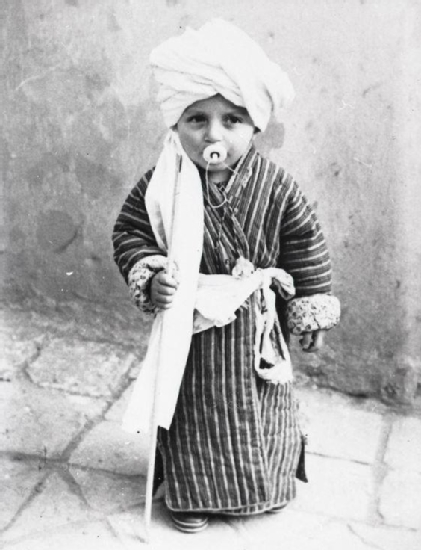

The basic costume for men, women, and children is made from lightweight cotton and consists of loose-fitting, long-sleeved shirts worn outside wide trousers (Pers. tanbān, ezār, Pashto partōg); the trousers are gathered on a drawstring (ezārband). The length of the typically collarless men’s shirt (perān, korta) is buttoned at one shoulder. The shirt varies from region to region, from knee to mid-calf or even lower. The finely embroidered Qandahāri shirt fronts (gaṛa, ganḍa) are renowned.

“There is shared core of the religion and the ceremonies,”Assaf-Shapira said of these Jewish communities. “But surrounding this shared core, there is a whole area of traditions which were shared with Muslims and Christians.”

Traditional clothing reflects geographic and residential variations. It also serves to express individual and group identity, social and economic status, and stages of the life-cycle. Changing sociopolitical trends ultimately lead to new styles, as well as to exchanges of clothing types. The terminology for all items of Afghan clothing varies widely. However, the central role of dress in Afghan culture is clear from the fact that new garments are essential for family, religious, and seasonal celebrations.

"Veiled Meanings: Fashioning Jewish Dress, from the Collection of The Israel Museum, Jerusalem

Daily Prayers And Unique Customs Connected With The Life Cycle

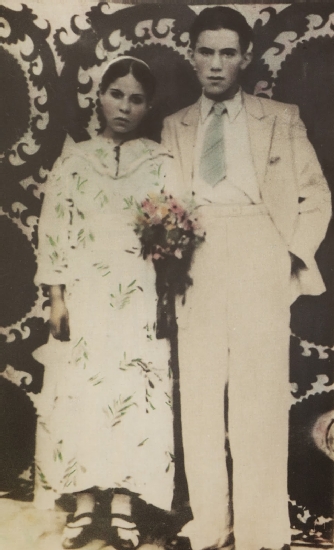

Jewish communities were regulated by daily prayers and the unique customs connected with the life cycle (circumcision ceremonies, bar mitzvahs, and weddings) and the major festivals (the Sabbath, the Day of Atonement, Tabernacles (Simhat Torah), and Hannukkah).[25]

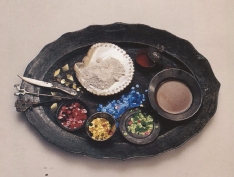

In his article "Henna in Herat (and Beyond): Jewish Henna Traditions of Afghanistan" the historian Noam Sienna from the Department of History at the University of Minnesota gives a vivid picture about Jewish life, especially the henna ceremony before a wedding, known as ḥanabandon ceremony and the Jewish henna traditions of Afghanistan. In his article he also cited the anthropologist Erich Brauer, who published important ethnographies of Yemenite and Kurdish Jews. Initially Brauer interviewed immigrants in Jerusalem and lately travelled to Afghanistan himself, in order to get an exact impression about the Afghans unique customs connected with the life cycle. In a short description written by Brauer one can follow the henna ceremony that takes place on the evening before the wedding, in the bride's house, but in seperate rooms:

Additionally, the bride's forehead will be decorated with sequins, thus carefully glued to her forehead in particular patterns. According to this unique custom the bride's whole forehead will be covered. There was a slightly different pattern for women who were in their first year of marriage.

One can follow this custom in vivid reconstructions (Fig. 30), that were done for the Israel Museum in the late 1970s by Malka Yezidi, Yokheved Merkhavi (each of whom had been a mashade in Herat), Rivqa Kohen (granddaughter of a Herati mashade), and Esther Betzalel.

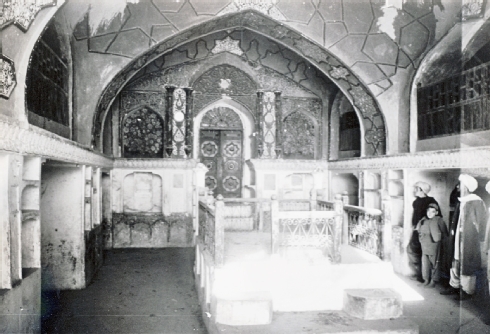

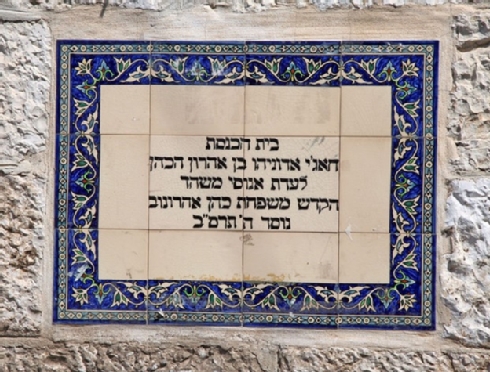

The Synagogues of Herat

Indeed, many other sacred buildings with beautiful interiors no longer exist due to a lack of maintenance. Fortunately, the Mullah Samuel or Shamawel Synagogue (ca. 1845–50), located directly opposite the market, was restored in 2009 during the Aga Khan Historic Cities Programme (AKHCP), supported by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture.[31] Following the principles of utilitarian “architectural repurposing” after its restoration in 2009, the building complex is used to house the Hariva School, a maktab (primary school)[32] for Muslim boys since 1978.[33] The Gol or Gulaki Synagogue was constructed in the late nineteenth century (specific dates unknown) as the private property of the wealthy upper-class Gol family. As such, the Gol Synagogue reflects the family’s exceptional status, patronage, and power. Restored in 2009 by the AKHCP, it has been converted into the Hazrat Belal Mosque, although it was probably used as a mosque as soon as the Jewish community left Herat in the late 1970s. The synagogue’s exceptional location in the Bar Durrani Quarter near the Royal Center with the Ikhtiyar al-Din Fortress and Citadel—coupled with its architecture and interior design—attest to different channels of communication and reciprocal influences between Herat’s Jewish community (especially its wealthier scions) and the Muslim majority. The Mullah Yoav Synagogue, built from 1788 through1808, was also abandoned in the late 1970s, but was already in disrepair by the time fighting broke out in the western quarter of the Old City after the 1978 uprising.[34] The restored Mullah Yoav Synagogue is now used as an educational center for children from the surrounding neighborhood, reflecting both the building’s adaptive use and the change the Jewish Quarter has undergone since its abandonment in the late 1970s.

While the dates when the four synagogues were constructed are known for certain (between the late eighteenth and early twentieth century), there is no documentation to show whether they were entirely new buildings for their time or were built over the ruins of older structures. Certainly, the Mullah Samuel Synagogue shows evidence of an earlier existence. If indeed these synagogues rose from pre-existing foundations, it is difficult to determine the form of the original building and the nature of the intermediate stages of construction.

The Jewish cemetery outside Herat's Old City

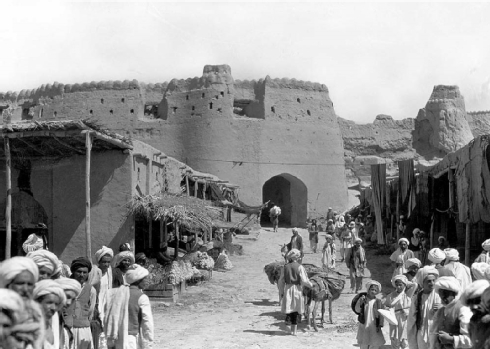

Herat's Old City

Herat—like other Islamic cities such as Aleppo, Cairo, Fez, Isfahan, Jeddah, and Sana’a—is the embodiment of a living city with traditional Islamic influences. Its architectural design was, for the most part, predetermined by Herat’s geometric urban concept and system, which was designed to meet the Islamic requirement to face toward Mecca (qibla). The city’s historic and vernacular architecture, and its exceptional surviving architectural heritage of both Muslim and non-Muslim origins, illustrate the complex processes of a global cultural transition. Herat, which is located in western Afghanistan and contains the most complete medieval vestiges surviving in the region, grew from a small fort founded in the 6th century BCE into a lively and dynamic city. The advent of Islam provided a new impetus for growth and importance in the walled city of Herat, which subsequently left an indelible mark on its physical form and structure. After its destruction at the hands of the Mongols, the city’s fortunes started to revive under the Kart dynasty (1245–1389 CE). As one of the most ancient cosmopolitan cities of central Asia—and an important stop along the Silk Road—it soon became the heart of the Timurid Empire (1405–1506 CE).[35] The Old City of Herat (or Harat), also referred to as the shar-i kuhna (“old town”), resembles a typical extended Afghan fortified town (qal’a).[36] Old Herat is defined by its unique culture and typical architecture reflecting a long tradition of building fortress houses or villages known as gala (Fig.1).[37]

The layout of the city has been documented and discussed in detail by the Afghan architect Abdul W. Najimi, in part based on historical- geographical illustrations by a Russian envoy to Herat and the map developed much later by Major General Oskar von Niedermayer (1885–1948).[38] The Old City forms a square with four main roads leading along the cardinal points dividing it into four identical quadrants. As such, Herat features a perfectly organized system based on orthogonal symmetry.[39] The old walled city (ca. 200 hectares)[40] and the surviving fabric of the residential and commercial quarters focused around three main points, the Commercial Center, known as Chahar Suq at the center of Herat; the Royal Center comprising the Fortress and Citadel (Qal'a-i Ikhtiyar al-Din); and the Religious Center containing the Masjid-i Jami (Friday Mosque). Herat’s geometrical urban organization, which will be analyzed through its Timurid architecture, probably originated in the eleventh century and is based on forms from the Ghaznavid dynasty (977– 1186 CE).[41] Specifically, it reflects a clearly structured urban geometry leading to the commercial royal, and religious centers. Herat’s design features axes and directions that, when possible, face Mecca, uniformly linking the physical to the sacred. The city’s town plan is based on the four-iwan building concept with one main hall (iwan) facing Mecca, Islam’s holiest city, flanked by three subordinate halls.[42] This architectural concept is based on the urban traditions of Herat’s Old City, and shares similarities with the design of a typical Arab town (medina).[43] The architect and planner Rafi Samizay performed a survey of Herat in 1977, listing the Friday Mosque, an Eidgah (a ceremonial square and associated mosque), eighty-two local mosques, three madrasas (religious schools), thirty-nine shrines, three synagogues, other religious edifices in three outlying suburbs such as the Timurid musalla (literally “place for prayer”),[44] as well as numerous other individual mosques that were constructed in close proximity to each other throughout the city.[45]

Herat, a UNESCO World Heritage Site (since Sept. 2004), in the fertile valley of Hari-Rud, was settled as early as the sixth-century B.C.E.The city is thought to have been established before 500 BC as the ancient Persian town of Artacoana or Aria. Alexander the Great besieged Herat in 330 BC during his campaign against the Achamenid Persian Empire. Known at the time as Artacoana, the city was rebuilt and called Alexandria of Aria. It is believed that a citadel was first established on its current site during this period. The city's older section is partially surrounded by the remains of massive mud walls, where several monuments still stand. Incorporated into the northern perimeter of the square walled city by the Ghaznavids, the Qal'a-i Ikhtiyar al-Din (a 15th-century citadel) stood witness to the changing fortunes of successive empires before being laid waste by Genghis Khan in 1222.[46]

The Masjid-i Jami (the Great Mosque) was the city's first congregational mosque, which contains examples of 12th-century Ghurid brick-work and 15th-16th century Timurid tilework. The Great Mosque was built on the site of two smaller Ghaznavid mosques; they were destroyed by earthquake and fire. The present Great Mosque was begun by the ruler of the Ghurid Empire, Ghiyath al-Din Muhammad b. Sam (1162-1202) in 1200 (597 AH). The mosque continued after his death by his brother and successor Shihab al-Din.[47] Herat city's other important monuments are located outside the walls: to the north of the Old City, the large artificial mound, known as Kuhandazh (or Kohandez), [48] the 15th-century Abu'l Qasim Shrine (variant names: Ziarar-i Shahzade Abu'l Qasim; Mazar-e Abu'l Qasim or Shahzada Kasim Mausoleum)[49] and the 15th-century Abdullah bin Muawiyah Shrine (variant names: Shrine of 'Abdullah bin Mu'awiyah;[50] Mazar-e Shahzade Abdullah or Shahzada Abdullah Mausoleum) built on the opposite side of the road. Farther to the north the Madrasah-i Gawhar Shad in the Musalla Complex, which was constructed between 1417-1438 (820-841 AH) according to its foundation plaque, now housed in the mausoleum. Only one minaret and the founder's mausoleum remain of the Madrasah-i Gawar ShadGawhar Shad.[51]

The Jewish Cemetery of Herat, Afghanistan

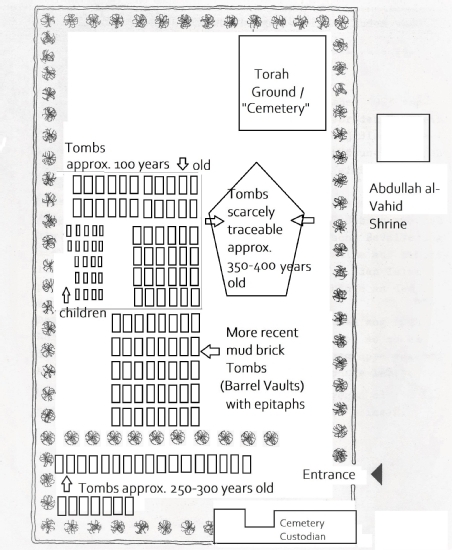

“In the afternoon of October 7th, 1973 we were accompanied to the old Jewish cemetery, which is about three kilometers outside the city. The cemetery, which roughly measures the size of a sports field, is surrounded by a mudbrick wall, on the inside of which trees are planted (Fig.35). Access is next to the simple mud -brick house, where a cemetery custodian lives with his family. Most of the area is flat and weakly covered with grass and low shrubs.

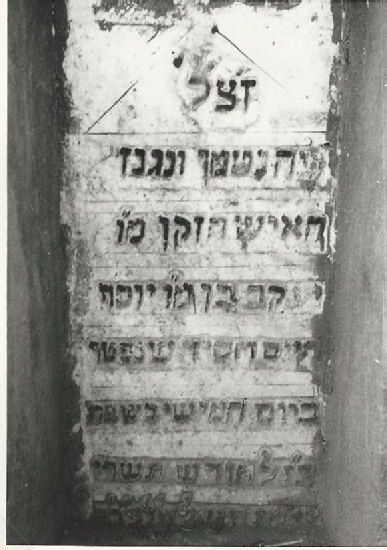

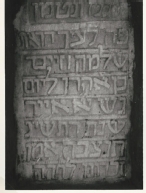

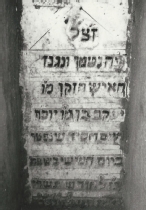

It is difficult to trace the oldest scarcely preserved tombs; their age is thought to be approximately 800 years (Fig. 35). A quarter of the territory shows poorly preserved burial sites (Fig. 36), the younger ones are furnished with epitaphs (Fig. 37)

In the corner opposite the mud-brick building there is a burial place for Torah scrolls (Fig. 37). The Torah scrolls out of use are not allowed to be destroyed, they will be buried in this place going along with a special ritual (cf. the famous Geniza of Cairo).“[54]

Indeed, in 1973 many of these important tombs, all of which are made of mud brick, no longer existed. Werner Herberg's sketch [57] of the Jewish cemetery with all documented traceable tombs (1973) reveals important insights. However, the figures referring to the age of the tombs (cf. 800 years) might be incorrect. The information is based on local oral tradition, there is a lack of documentation. The age of the mud-brick tombs can be specified with a period of approximately 100 up to 250-300 years or even approximately up to 350-400 years:

- about 18 tombs dedicated to adults (approx. 250-300 years old)

- about 40 more recent tombs (barrel vaults) featuring epitaphs dedicated to adults

- about 34 tombs dedicated to children (approx. 100 years old)

- about 46 tombs dedicated to adults (approx. 100 years old)

- tombs scarcely traceable (approx. 350-400 years old)

This Jewish cemetery of Herat certainly contains some of the most important Hebrew-Persian inscriptions found in Herat, Afghanistan. All of the tombs were built in commemoration of members belonging to the Jewish-Persian community, which definitely spanned several generations. The population of this Judaeo-Persian speaking community seems to have been grown significantly during the last 200-300 years. The increasing presence of hundreds of Jewish families in Herat - many were immigrants from the Jewish community of Mashhad founded during the reign of the Persian ruler Nadir Shah (r. 1736-47),[55] who was known for his tolerance toward Jews - helped strengthen existing Jewish institutions and contributed to the flowering of Jewish life in Afghanistan.

Epitaphs from the Jewish Cemetery in Herat

Saving Cultural Heritage - "The Herat Jewish Cemetery Project"

Due to the current warfare in Afghanistan, no further investigation at the Jewish cemetery could be undertaken, since the "Herat Cemetery Project" started in 2015: the Jewish cemetery was secured with a new wall, the ground and graves were cleaned from rubbish. A great part of the traceable tombs was restored and the epitaphs saved from decay (Fig.39-41).

Future research and fieldwork could shed further light on many of the important questions raised and might reveal the social and ethnic background of the deceased more clearly. How did the Jewish community come to live at Herat? Future archaeological findings in the region would help to document the origin of the Judaeo-Persian speakers in Afghanistan. That is another compelling reason to hope for a future peace in Afghanistan and its surrounding regions.

[1] Raverty, H.G. Tabakāt-i-Nāsirī: A General History of the Muhammadan Dynasties of Asia, Including Hindustan; from A.H. 194 (810 A.D.) to A.H. 658 (1260 A.D.) and the Irruption of the Infidel Mughals into Islam by Minhāj-ud-Dīn Abū- ‘Umar-i-‘Usmān Maulānā Juzjani. Vol.1. Calcutta: The Asiatic Society, 2010, 313-315

[2] Niẓām al-Mulk, Abū ʿAlı̄ Ḥasan ibn ʿAlı̄, 'Siyásat-náma',Traité de gouvernement: Siyaset-Name composé pour le sultan Malik Chah, traduit du persan et annoté par Charles Schefer et préfacé par Jean-Paul Roux (Paris: Sindbad, 1984), 138-205 (139).

[3] The historical term ‘dhimmī’ (Arabic: ذمي ) refers to non-Muslim subjects of a Muslim state who were "second- class" citizens deprived of social and political equality by contract

[4] The son of the first Saljuq ruler of Khorasan, Čaḡrī Beg Dāwūd, brother of Ṭoḡrel, the first sultan of the Great Saljuqs of Iraq and Iran. See K. A. Luther, “ALP ARSLĀN: Saljuq sultan from 455/1063 to 465/1072,” Encyclopaedia Iranica, vol. 8-9 (1985): 895-898, http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/alp-arslan-saljuq-sultan .

[5] Browne, Edward G. A Literary History of Persia, vol. II: From Firdawsi to Sa’di. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009, 214.

[6] Walter J. Fischel, “Persia,” Jewish Virtual Library, 2008 http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/judaica/ejud_0002_0015_0_15625.html

[7] A Persian prose work written in the 6th/12th century by Abu’l-Ḥasan Neẓām-al-Dīn (or Najm-al-Dīn), Aḥmad b., ʿOmar b., ʿAlī Neẓāmī, ʿArūżī Samarqandī, originally entitled Majmaʿ al-nawāder. See Ḡolām-Ḥosayn Yūsofī, “ČAHĀR MAQĀLA,” Encyclopaedia Iranica, vol. 4:6 (1990): 621-623, online: http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/caharmaqala .

[8] Browne 2009, 336.

[9] His name can also be spelled as Nidhámí-i-'Arúḍi. The reference is in Anecdote XXII of the ‘Third Discourse on Astrologers.’ See Ferdinand Wüstenfeld, Geschichte der arabischen Aerzte und Naturforscher (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht, 1840).

[10] Edward G. Browne, Revised Translation of the Chahár Maqála ("Four Discourses") of Niẓámí - I- 'Arúḍí of Samarqand. Followed by an Abridged Translation of Mírzá Muḥammad's Notes to the Persian Text (London: Cambridge University Press, 1921), 64 and note 1.

[11] David C. Thomas, The ebb and flow of an empire: the Ghūrid polity of central Afghanistan in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, vol. 1 (Bundoora, Victoria: La Trobe University, 2011), 87.

[12] Thomas 2011, vol. 2, 376-392.

[13] Clifford E. Bosworth, The New Islamic Dynasties: A Chronological and Genealogical Manual (Edinburgh: University Press Ltd., 1967); Clifford E. Bosworth, “The Early Islamic history of Ghur,” Central Asiatic Journal, vol. 6 (1961): 116-133.

[14] Ulrike-Christiane Lintz, “The Qur'anic Inscriptions of the Minaret of Jam in Afghanistan,“ in: Calligraphy and Architecture, ed. Mohammad Gharipour and Irvin Cemil Schick (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2013), 83-102.

[15] Raverty 2010,vol. 1, 339.

[16] Browne 2009, 340.

[17] Bosworth, Clifford E., “The Early Islamic history of Ghur.” Central Asiatic Journal 6 (1961): 116-133 (121-124); Pinder-Wilson, Ralph. “Ghaznavid and Ghūrid Minarets.” Iran: Journal of the British Institute of Persian Studies 39 (2001): 155-186; Nizami, Khaliq A. “The Ghurids.” In Muhammad S. Asimov and Clifford E. Bosworth, ed., History of civilizations of Central Asia, vol. IV: The age of achievement: A.D. 750 to the end of the fifteenth century. Part 1: The historical, social and economic setting. Paris: UNESCO Publishin178. Not in Bibliography 1998.

[18] Pinder-Wilson 2001, 155-186 (124,180); Nahid Pirnazar, Voluntary Cenversions of Iranian Jews in the Nineteenth Century, Iran Namag 4:2 (Summer 2019); Heshmat Allah Kermanshahchi, Iranian Jewish Community: Social Developments in the Twentieth Century (Los Angeles, Ketab Corporation, 2007), 347-350; Mehrdad Amanat, Negotiating Identities, Iranian Jews, Muslims and Baha'is in the Memoirs of Rayhan Rayhani (1859-1939), Ph. D. Dissertation (Los Angeles: University of California, 2006), 107, 146-47; Habib Levi, Trkh-e Yahd-e Irn, 2nd ed., vol.3 (Beverly Hills: Iranian Jewish Cultural Organization of California, 1984), 668-669 (635), 744-747, reporting from the memoirs of Rahim Misha'il. In 1892, Zulaykha, the wife of Zaghi, converted to Islam in order to gt divorced. She married the Muslim clergyman who right away claimed all the property of Zaghi for Zulaykha according to the Law of Aposty.

[19] Susan Gilson Miller, Attilio Petruccioli, and Mauro Bertagnin, “Inscribing Minority Space in the Islamic City: The Jewish Quarter of Fez (1438–1912),” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 60, no. 3 (September, 2001): 310–327.

[20] Daniel Tsadik, “Judeo-Persian Communities of Iran: V. Quajar Period (1876–1925),” in Encyclopaedia Iranica (2012): http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/judeo-persian-communities-v-qajar-period# ; idem , Between Foreigners and Shi’is: Nineteenth-Century Iran and its Jewish Minority, 36, 81 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2007), 121.

[21] Abigail Green, “Old Networks, New Connections: The Emergence of the Jewish International,” In Green and Viaene, Religious Internationals in the Modern World, 113.

[22] Jack, Joseph, and Morton Mandel Wing for Jewish Art & Life: Costume and Jewelry: A Matter of Identity, The Israel Museum: Permanent Exhibitions.

[23] In contrast, the Jews of Balkh lived along one street, and their quarter was “closed in by a gate, locked every evening caused by security reasons and shut up on a Sabbath-day”; Joseph Wolff, Researches and Missionary Labours Among the Jews, Mohammedans and Other Sects, During His Travels Between the Year 1831 and 1834 (London: James Nisbet & Co., 1837), 209.

[24] Najimi, Herat: The Islamic City, 45, Fig. 3, 13.

[25] Hanegbi and Yaniv, Afghanistan, 28–39.

[26] The mikva (plural: mikva’ot): a bath used for the purpose of ritual immersion and ablution in Judaism to achieve ritual purity.

[27] Samizay, Islamic Architecture in Herat, 210.

[28] Samizay, “Herat: Pearl of Khurasan,” 92.

[29] Samizay, Islamic Architecture in Herat, 174.

[30] Hanegbi and Yaniv, Afghanistan, 18.

[31] “Hariva School: Herat, Afghanistan,” Archnet, http://archnet.org/sites/14829 (accessed October 5, 2016)

[32] See “maktab,” in Encyclopaedia Britannica (2014).

[33] “Hariva School: Herat, Afghanistan.”

[34] See “Afghanistan: Kabul and Herat Area Development Projects,” Aga Khan Trust for Culture Historic Cities Programme, http://www.akdn.org

[35] Samizay, “Herat: Pearl of Khurasan,” 86–99; See also David C. Thomas, “The Ebb and Flow of an Empire: The Ghurid Polity of Central Afghanistan in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries” (Ph.D. diss., La Trobe University, 2011).

[36] Warwick Ball, The Monuments of Afghanistan: History, Archaeology and Architecture (London: I. B. Tauris, 2008).

[37] Anette Gangler, Heinz Gaube, and Attilio Petruccioli, Bukhara: The Eastern Dome of Islam; Urban Space, Architecture, and Population (Stuttgart: Axel Menges, 2004), 35–37.

[38] Abdul Wasay Najimi, Herat: The Islamic City; A Study in Urban Conservation (London: Curzon Press, 1988), 36–37 and Figs. 3.2, 3.3; Oskar von Niedermayer, Afghanistan (Leipzig: Verlag Karl W. Hiersemann, 1924), Plan 3.

[39] Elena Georgieva Paskaleva, “The Architecture of the Four-Iwan Building Tradition as a Representation of Paradise and Dynastic Power Aspirations” (Ph.D. diss., Leiden University, 2010), 133; see also Rafi Samizay, “Herat: Pearl of Khurasan,” Environmental Design: Journal of the Islamic Environmental Design Research Centre 1–2 (1987): 86–93.

[40] Four walls of about half of a farsakh (three miles) each, forming a rough square; Maria Szuppe, “Herat,” in Encyclopaedia Iranica, 211–217, http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/herat-iv ; Samizay, “Herat: Pearl of Khurasan,” 88.

[41] Paskaleva, “The Architecture of the Four-Iwan Building Tradition,” 133.

[42] Vincent J. Cornell, Voices of Islam, vol. 4, Voices of Art, Beauty, and Science (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2007), 94–95; Cenk Yoldas, A Prototypical (School) Design Strategy for Soil–Cement Construction in Afghanistan (Manhattan, KS: Kansas State University Press, 2004).

[43] Samizay, “Herat: Pearl of Khurasan,” 88; Najimi, Herat: The Islamic City, 94–95.

[44] Musalla is a large open-air gathering place for Muslim worship, especially for the two major annual festivals.

[45] Samizay, Islamic Architecture in Herat, 114–115; idem, “Herat: Pearl of Khurasan,” 90

(46) archnet.org/sites/6834

[47] archnet.org/sites/3931

[48] archnet.org/sites/3934

[49] archnet.org/sites/5417

[50] archnet.org/sites/ 5551

[51] archnet.org/sites/ 5415

[52] archnet.org/sites/ 5552

[53] Werner Herberg, Forschungsreise 1973 nach Afghanistan (unpublished document)

[54] translation by the author

[55] “Nadir Shah,” Encyclopaedia Britannica. Nadir Shah (1688–1747) was an Iranian ruler, and conqueror who created an Iranian empire that stretched from the Indus River to the Caucasus Mountains, http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/401451/Nadir-Shah .

[56] Werner Herberg, Forschungsreise 1973 nach Afghanistan (unpublished document); David Yeroushalmi. The Jews of Iran in the Nineteenth Century. Leiden: Brill , 2010, 31-32 n12; 32 n13, 33, 247 n9. Ulrike-Christiane Lintz, Reflection of Sacred Realities in Urban Contexts: The Synagogues of Herat." In Mohammad Gharipour, ed., Synagogues in the Islamic Word, Architecture, Design, and Identity. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2017, 51-72 (with a detailed documentation of Herat's Jewish community).

[57] Zohar Hanegbi and Bracha Yaniv, Afghanistan: The Synagogue and the Jewish Home (Jerusalem: Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 1991), 13–17.

[58] Fotos made by Werner Herberg in Herat, Afghanistan 1973 (courtesy of Werner Herberg) copyright www.museo-on.com

Further Reading:

- Bezalel, Izhak. A Community of its Own: The Jews of Afghanistan and their Classification between the Jews of Iran and Bukhara, Pe'amim 79 (1999): 15-40 (in Hebrew).

- Sabar, Shalom. The Origins of the illustrated Ketubbah in Iran and Afghanistan, Pe'amim 79 (1999): 129-158 (in Hebrew).

- Seroussi, Edwin and Davidoff, Boaz. On the Stuy of the Musical Tradition of the Jews of Afghanistan, Pe'amim 79 (1999): 159-170 (in Hebrew).

- Shaked, Shaul. New Data on the Jews of Afghanistan in the Middle Ages, Pe'amim 79 (1999): 5-14 (in Hebrew).

- Yaniv, Bracha. Content and Form in the Flat Torah Finials from Eastern Iran and Afghanistan, Pe'amim 79 (1999): 96-128 (in Hebrew).

- Mishael, Yisrael. Bein afganistan le-ereṣ yisrael: mizikhronotav shel nesi haqehila biṣefon afganistan. Jerusalem: Ministry of Education and Culture, 1980.

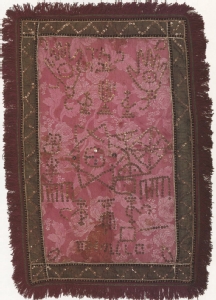

![Fig. 29 Close-up of Afghan ketubba [wedding certificate], Herat, 1812](/go/museoon/_ws/mediabase/_ts_1642951528000/generated/modules/sites/website/pages/home/projekte/jewishcemetery_heratafghanistan/main/_page_id_o_advanced_529/de/pic01_490x550.jpg)